In South Korea, the word chaebol evokes mixed emotions admiration, pride, frustration, and resentment. These family-owned industrial conglomerates such as Samsung, Hyundai, and SK have played a pivotal role in transforming the country from a war-torn state into a global economic powerhouse. But today, the dominance of chaebol in South Korea’s economy and society is increasingly being scrutinized.

The Rise of Chaebol: From Ruins to Riches

Emerging in the 1960s and 1970s during President Park Chung-hee’s administration, chaebol were built through government-directed industrial policies. They received massive state support in exchange for achieving national export goals. Companies were assigned specific industries—Hyundai with cars, Samsung with electronics—and rewarded for performance.

This symbiotic relationship led to unprecedented industrial growth. By 2022, the five largest chaebol accounted for around 45% of South Korea’s GDP, with Samsung alone contributing nearly a quarter. The intertwining of national success with chaebol prosperity created what Professor Jang Ha-seong calls a “chaebol obsession.”

Culture, Media, and the Myth of the Chaebol

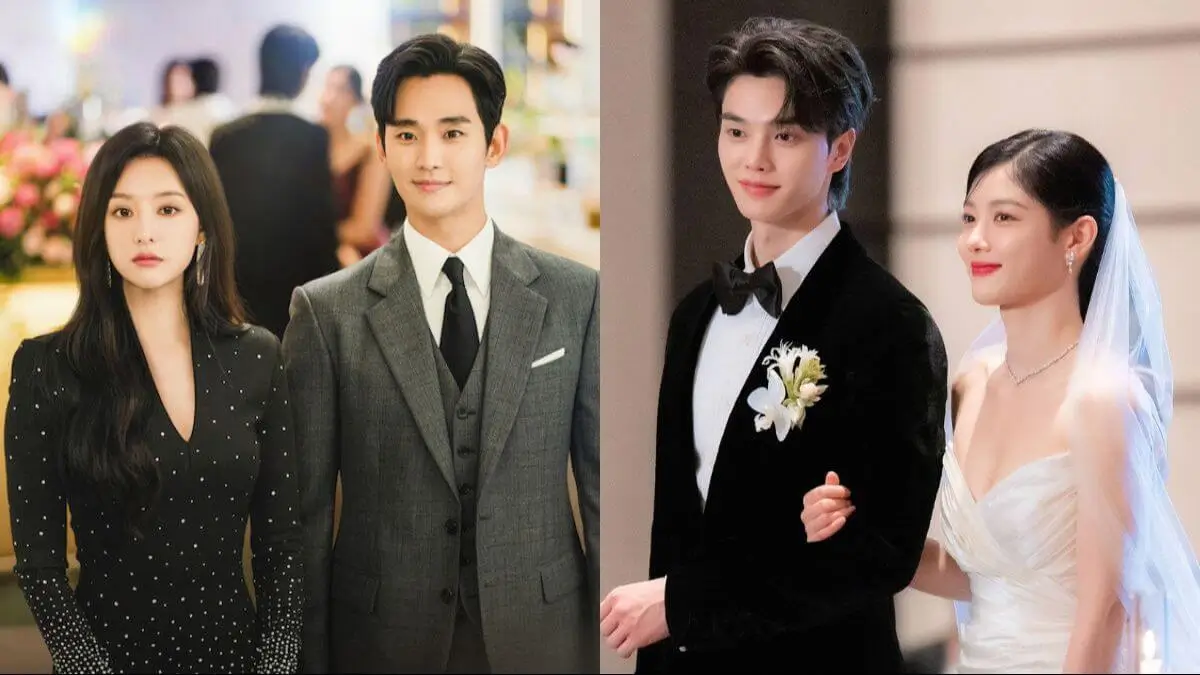

The influence of chaebol extends beyond economics. On streaming platforms like Netflix and Disney+, Korean dramas often revolve around chaebol heirs entangled in romance and corporate intrigue. These portrayals glamorize inherited wealth and social privilege, embedding the chaebol ideal into popular imagination.

Professor Park Sang-In of Seoul National University warns against such romanticization, saying it normalizes privilege and erodes meritocratic values. “It suggests that success depends more on your birth than your ability, which is a dangerous message for the youth,” he notes.

Labor Inequality and Market Distortion

For many young South Koreans, securing a job at a chaebol is the ultimate career goal. The prestige and pay are unmatched but the competition is fierce. This dynamic creates a bifurcated labor market, where top talent is absorbed by chaebol, leaving SMEs (small and medium enterprises) struggling.

In 2022, employees at SMEs earned only 63% of what their chaebol counterparts made, according to OECD data. The result is both economic distortion and growing disillusionment among the youth.

Structural Challenges and Calls for Reform

Despite decades of reform attempts, chaebol still operate with opaque ownership structures and limited accountability. Ownership loops and cross-shareholding allow families to control vast empires with minimal equity 10 top chaebol leaders hold 55.7% voting rights with only 0.9% of actual shares, according to the Korea Development Institute.

Reforms proposed during the Moon Jae-in administration aimed at increasing transparency largely failed due to reliance on voluntary compliance and insufficient legal enforcement.

South Korea’s chaebol stand at a crossroads. Their past contributions to national growth are undeniable, but their future role is being questioned. “Chaebol built Korea,” says Professor Park. “But unless we reform how they function and interact with society, they may end up holding Korea back.”

Public trust, especially from the younger generation and foreign investors who own roughly 30% of Korean stocks, will be essential. As globalization and digital transformation redefine competitive advantages, chaebol must evolve or risk becoming relics of a bygone era.